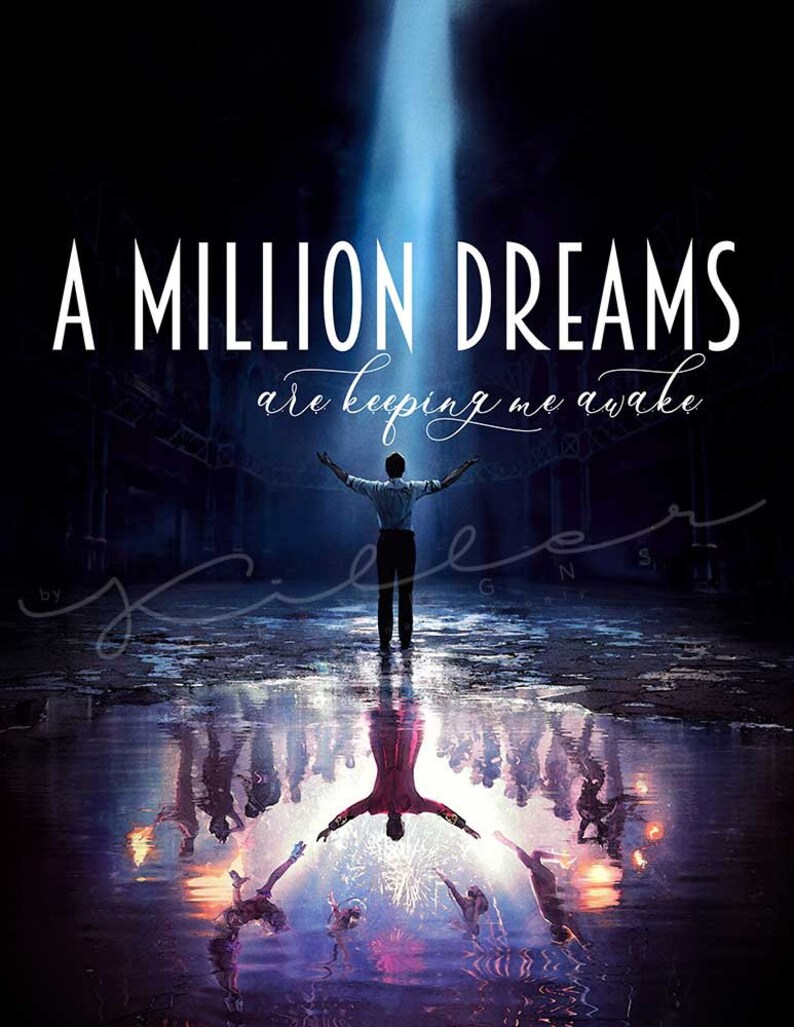

I think my favourite song from The Greatest Showman is probably ‘A Million Dreams’. It’s sung by the young PT Barnum, and then the adult one. I find it such a poignant and powerful song, full of meaning. People who know me well may recognise why this song in particular speaks to me: I’m a dreamer. I readily identify with the sentiment of the chorus:

“Every night I lie in bed, the

brightest colours fill my head,

A million dreams are keeping me

awake.

I think of what the world could

be, a vision of the one I see,

A million dreams is all it’s

gonna take –

A million dreams for the world we’re

gonna make…”

I’m especially struck by that second part, about what the

world could be. That’s my story, this is

my song. It’s like the famous saying by

George Bernard Shaw, “You see things; and you say, ‘Why?’ But I dream things that never were; and I

say, ‘Why not?’”

In the song ‘A Million

Dreams’, young Barnum is open to the possibility that people will call him

crazy, and say he’s lost his mind. The

echoes of Jesus and his story are loud and clear. People said Jesus had “gone out of his mind”

(Mark 3:21) – his own family, no less – in view of his attracting large crowds who

wanted their lives and their world to be better, so they came to Jesus for

healing, and to hear his incredible teaching.

Stories of a better world.

Pictures of how life can be. In fact,

in Mark’s story of Jesus, immediately after that incident of Jesus being insulted

by his relatives, he launches into a set of stories about God’s kingdom (Mark

4:1-34 – it’s paralleled in Matthew’s account, mostly in chapter 13). These parables, as they are called, paint a

radically inclusive, gently influential way of life, an alternative reality. This is the reality that comes about when the

life presented by Jesus in his ‘Sermon on the Mount’ (and modelled by Jesus) is

taken seriously and actually lived (or at least aimed at).

To many (probably

most) people, it all sounds crazy. Loving

enemies. Not getting angry at people. Turning the other cheek. Not worrying about… well, anything, really –

but trusting in God’s providence of the necessities of life. Not judging others. Treating people the way you’d hope to be treated. Generally making choices that promote life

and not death. Maybe it is crazy. A pipe dream.

But it’s Jesus’ dream, of what the world could be.

“A million dreams is

all it’s gonna take. A million dreams for

the world we’re gonna make.”